Decades of support to the Ju/'hoan San

Please download the 2018 brochure "Water, Land and a Voice".

Content

- Brief history of the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia

- The Ju/’Hoansi of Nyae Nyae

- Who are the San in Namibia

References & Suggested further reading

Forword

I first visited Nyae Nyae in the mid-1980s and have been back many times in different capacities – as a journalist, government official, tourist and environment and development consultant. Over the years I have seen changes in the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN) and in the development trajectory of the people it supports.I first visited Nyae Nyae in the mid-1980s and have been back many times in different capacities – as a journalist, government official, tourist and environment and development consultant. Over the years I have seen changes in the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN) and in the development trajectory of the people it supports.

In 2012 I became the Chairperson of the NNDFN board, giving me the opportunity to observe more closely the work it is doing. In 2016 we decided to have a Board meeting in Tsumkwe and visit some of the villages where agriculture and livestock activities were being implemented. We visited two different villages in the evening (Kaptein Pos and Mountain Pos) and I was pleased to see herders bring their cattle home to their kraal to overnight and lion-proof kraals being built to protect the animals. There was also a reliable source of water protected from damage by elephants.

This seemed a world away from the 1990s when donated cattle were untended, were regularly lost to predators and residents struggled to access clean water. So I asked the secretariat of NNDFN to look into doing a longer-term review of progress, rather than the very short-term project based reviews which are the norm, to see what and why such significant changes were happening now.

While there is still so very far to go for the San to be on par with other communities in Namibia in terms of their access to social services, education levels, and job opportunities it is rewarding to see some real progress being achieved. This book provides an insight into the challenges, failures and successes of the organisation over the past 36 years.

Brian JonesChairperson,

NNDFN

Executive Summary

Water, Land and a Voice reflects on the support provided by the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN) to the Ju/’hoan San in north-eastern Namibia over the last 36 years. The aim is to highlight positive, constructive areas of development and lessons learned along the way. This is not an academic publication or detailed project review, rather an attempt to see the big picture and reflect on progress made and the challenges that still remain.

Water, Land and a Voice reflects the core concerns of the Ju/’hoansi: Water, because of the critical role played by a reliable water resource in enabling the Ju/’hoansi to move back to their ancestral land and survive there; Land, because of the importance of secure land tenure for the future of the Ju/’hoansi and their right to self-determination; and a Voice, because of the significant role played by the NNDFN (and many others) in providing a development and advocacy structure and enabling the Ju/’hoansi in Namibia to acquire an independent voice of their own.

NNDFN and its development partners have worked on a diverse range of projects from water supply, organisational/leadership development, community-based natural resource management, agriculture and livestock, livelihoods, primary healthcare, HIV & AIDS awareness, village schools and craft. Rather than detail those projects, this publication aims to shed light on why some activities worked at a particular time, but not beforehand, and on how insights emerging from this have resulted in enhanced and a more sustainable uptake of the support being provided.

A. NNDFN

The origins of what is today known as the NNDFN can be traced to the initial visits by the Marshall family from the United States to the Nyae Nyae area in the early 1950s. However, it was only in the 1970’s when the Ju/’hoansi territory had, as a result of a number of events, been reduced to about a tenth of its original size that they found themselves being essentially confined to residing in the settlement of Tsumkwe. Driven by the abysmal living conditions in Tsumkwe, the Ju/’hoansi were motivated to move back to their traditional land. This was the catalyst for the formation of the Cattle Fund in 1981, which was the precursor for NNDFN. The organisation was set to support the Ju/’hoansi to move back to the land by assisting with the provision of permanent, equipped water points in the n!oresi they once inhabited.

B. Water

Assisting the Ju/’hoansi to move back to their land in the 1980’s was not sufficient; livelihoods also needed to be addressed in order for the Ju/’hoansi to sustain themselves and remain permanently settled in their n!oresi. The establishment of dryland crop fields, vegetable gardens and the provision of livestock (cattle) were thus priorities for NNDFN, but were mostly unsuccessful at that time, largely due to the limited water supply which was often interrupted when elephant damaged the water infrastructure and equipment as well as the fact that many Ju/’hoansi then had very little or no prior experience in agriculture.

Today, however, there is a renewed interest in establishing vegetable gardens in many of the villages in Nyae Nyae. A number of critical factors have contributed to this. The NNDFN embarked on a massive undertaking to ensure that village water sources were adequately protected against potential elephant damage and that each village was equipped with adequate water storage facilities. Support in establishing gardens is now given to individuals and households that show an interest and the focus is on low maintenance, high yield crops that are culturally close to the norms of the San. The provision of hands-on training and regular ongoing back-up has contributed greatly to the shift in attitudes towards agricultural activities by the Ju/’hoansi resulting in more uptake and sustainability.

Similarly, NNDFN has supported numerous livestock initiatives with the aim of enabling the Ju/’hoansi to subsist at a village level. Since the formation of the Cattle Fund, the Ju/’hoansi have acquired livestock, mainly cattle, provided by various support organisations or purchased by the San themselves. However, attempts to stimulate sound livestock management practices were met with varying levels of success, again a significant contributing factor was the lack of reliable water alongside a lack of animal husbandry skills.

More recently, however, there has been an increased interest and participation in livestock farming by the Ju/’hoansi, largely as a result of a shift in approach towards holistic rangeland management principles. The overall purpose of this approach is to improve livestock health, fertility, genetic mix, prevent overgrazing and herd livestock. This has resulted in reduced calf mortality, reduced deaths from predators and poisonous plants and improved overall livestock health leading to larger, more productive herds.

C. Land

The NNDFN has, since its formation, always seen access to the ancestral land the Ju/’hoansi have inhabited for millennia, as a critical foundation for them to be able to assert their right to self-determination in a suitable and sustainable way. Initially, the focus was on enabling the Ju/’hoansi to permanently sustain themselves in their n!oresi largely based on “farming”, thus securing the land. However, this gave no legal protection of their rights, so there was a shift towards Community-Based Natural Resource Management and the formation of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in June 1998. This provided the Ju/’hoansi with management, benefit and utilisation rights over wildlife- and tourism-related activities. To further strengthen the legislation protecting their rights, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy area was gazetted as a Community Forest in March 2013 which provides a mechanism to utilise and protect forest resources including grazing. In addition, the official recognition of the Ju/’hoansi Traditional Authority in 1998 also contributed to enabling the Ju/’hoansi to assert a certain level of “rights” over the area of Nyae Nyae.

D. Voice

NNDFN has also played a role in ensuring that the voice of the Ju/’hoansi is heard, initially by being the voice, then coaching and encouraging the Ju/’hoansi voice and ultimately supporting the creation of formal structures such as the conservancy and community forest that provide forums for discussions and representation. This is particularly critical in addressing land and resource rights infringements which require formal engagement with authorities. Hierarchical structures and confrontation are not the cultural norms of the San and this has weakened their position in the hierarchical and political environment that they now find themselves having to navigate.

It is also critical that stakeholders do not assume the responsibility of speaking on behalf of the Ju/’hoansi. It is essential that the Ju/’hoansi speak for themselves and that their leaders are encouraged to persist in asserting themselves.

In more recent times the media has played an increasing role in profiling the San and their issues and this has been found to be an effective way of motivating the authorities to respond.

E. Lessons

Within the context of this publication the role of the NNDFN in its enabling and supportive relationship with the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae over the last 36 years has demonstrated a number of key lessons.

- Development cannot be measured in project cycles. An important reflection that emerges from this publication is that the consistency of ongoing support provided by the NNDFN over the last 36 years as a whole is more significant than the outcomes of individual programmes. Change does not happen overnight.

- The timing and method of implementation of different projects is crucial. There are multifaceted, cultural issues at play that have a considerable influence over the outcome of any individual project within the overall support programme. A project implemented at one time may yield a different outcome to the same project implemented at a different time e.g. agricultural projects have proven to be much more successful following years of investment in water infrastructure.

- Some areas of project support do not always lend themselves to a blanket approach. The focus of some NNDFN projects has shifted from community-wide support to more targeted support to individuals and households showing commitment, resulting in a clear improvement in outcomes. There is a need to remain flexible and learn from the implementation of different projects, and adapt the approach in response to what is learnt and what is needed.

- Focus on a few essential areas of development, for a sustained period in order to create real change.

F. Challenges

This publication also identifies challenges that NNDFN and the Ju/’hoansi themselves will need to address if there is to be any long-term progress towards the goal of their not only surviving, but prospering on the land of their ancestors.

- Security of land tenure is essential for the Ju/’hoansi to integrate as equal, fully participating partners in the broader Namibian society. The Ju/’hoansi are a community in transition, undergoing changes in the span of a single generation and how the community and its partners deal with this will influence their future survival. Security of land tenure will be key to determining the future of the Ju/’hoansi, particularly how the current threat to their land by illegal grazing is dealt with by the community and authorities.

- Creating a shared understanding and vision of what constitutes “development” in the Nyae Nyae area. Development cannot be understood in isolation, as it is multi-faceted, and involves different development partners whose respective agendas might not always perfectly overlap and allowing for adaptation given unforeseen consequences of some “development” actions.

- Ensuring stakeholders do not assume the responsibility that rightfully resides with the Ju/’hoansi themselves. In this regard it is vital that the Ju/’hoansi and their leadership are encouraged to persist in asserting themselves and voicing their opinions even if they conflict with the views of others. This is a particular challenge to a community that traditionally did not have a leadership hierarchy.

- Ensuring sustainable water and food security is essential in creating greater independence in the community. Climate change is also likely to negatively affect the availability of veld food, which still plays a critical role in providing much-needed nutrition. Food security is not only about vegetable gardens or livestock; the challenge is also about being able to identify other opportunities through which the Ju/’hoansi can be empowered to take the lead in improving their livelihoods.

- Finally, in order to ensure continuity in its provision of support, the NNDFN must face the challenge of securing funding for the foreseeable future, so that it can continue to be a voice for the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae and in so doing create an enabling environment for the Ju/’hoansi in Namibia to fully develop an independent voice of their own.

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief history of the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia

The origins of what is today known as the NNDFN can be traced to the initial visits by the Marshall family from the United States to the Nyae Nyae area in the early 1950s (see further reading list). These and subsequent contacts led to the establishment of the Cattle Fund in 1981. A voice was born.

The Cattle Fund soon thereafter was renamed as the Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation (JBDF), which was set up to administer the fund itself. Ten years later, after Namibia had gained its independence from South Africa, the JBDF changed its name to better reflect the new realities in Namibia, and to remove the word ‘Bushman’, considered by some to be derogatory, to the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia. N//oaq!áe (Nyae Nyae) is the name given by the Ju/’hoansi to the area in which they lived, which had been their home since time immemorial.

From 1981 until early 1991, the JBDF had based its operations in Nyae Nyae from a village called /Aotcha, mainly because of the important links that had been formed with some Ju/’hoansi members who had been instrumental in advocating a return to the land in the late 1970s. By the late 1980s, there were approximately 30 villages that had been resettled, all needing support in one form or another, as these communities struggled to establish livelihoods that would enable them to stay on the land. This arrangement was hampered by logistical challenges, diminishing the effectiveness of the support, and the fairness with which it could be delivered. In addition, there were other social dynamics associated with the foundation being linked to a particular village, resulting in consideration being given to relocating JBDF operations. A comprehensive proposal to establish an independent stand-alone training centre was developed. Funding was secured, and a training centre was established at Baraka, becoming operational in early 1991. The Baraka n!ore was not inhabited by anyone at that stage. (A n!ore (plural: n!oresi) can be translated as a resource area; more detailed information on n!oresi is provided below.)

Securing funding for the comprehensive development programme became increasingly difficult. At the same time, changes in the management and support focus areas and the establishment of a Nyae Nyae conservancy office in Tsumkwe in the early 2000s resulted in Baraka becoming less viable as a centre of operation. In September 2002 the board of the NNDFN took a decision to hand the Baraka Training Centre over to the Nyae Nyae Conservancy (NNC), although both NNDFN and NNC staff were still accommodated at Baraka from where support was provided until late 2007. By then, the number of NNDFN staff, particularly expatriate staff had been reduced quite significantly. More recently, additional support was shifted to Tsumkwe, where today the NNDFN has a small office with staff and accommodation facilities. Most activities undertaken in Nyae Nyae are implemented by a full-time field manager, with additional support being provided by NNDFN staff and specialist consultants (e.g. Devils Claw, Permaculture, Legal) operating out of the Windhoek office.

The aim of the NNDFN over this time has remained the same and is reflected in its constitution to provide support to the Ju/’hoan San in the fields of land and human rights, and the sustainable use of natural resources, with the goal of empowering them to improve their quality of life both economically and socially. The basis for the achievement of this goal is provided for in the core objectives of the NNDFN, which centre on working towards the organisational autonomy of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy and Community Forest (NNCCF) and improved livelihoods through.

1.2. The Ju/’Hoansi of Nyae Nyae

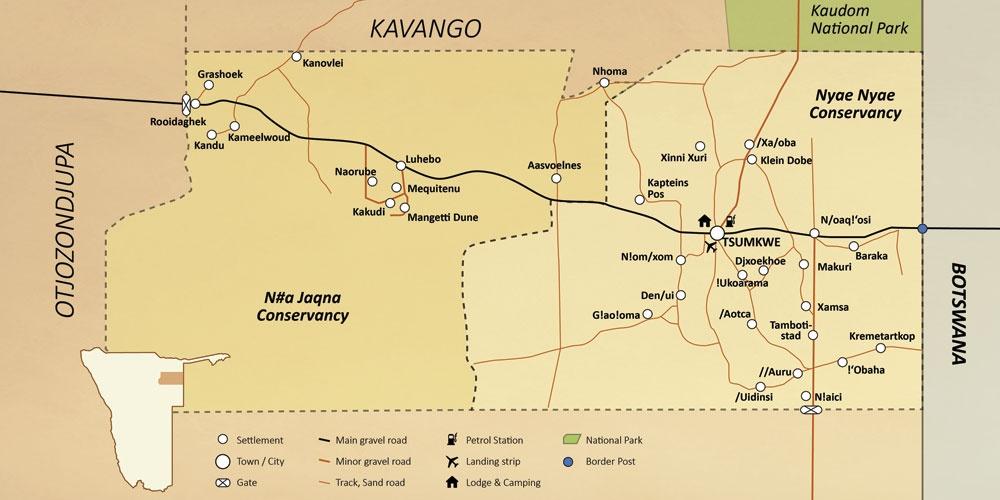

The Ju/’hoan, meaning “true or ordinary people”, live in the area called Nyae Nyae. It is located in the Otjozondjupa region of Namibia, in the Tsumkwe East Magisterial District on the border with Botswana; in their language, the area is referred to as N//oaq!áe, meaning “place of broken rocks”.

The Ju/’hoansi are the second largest group of San people in Namibia. There are widely differing estimates of the exact number of Ju/’hoansi. However, it is probably safe to say that there are about 5 000 – 6 000 Ju/’hoansi living in Namibia, with another 5 000 or so living in Botswana. Some sources suggest that before 1960, there might only have been about 250 Ju/’hoansi living semi-permanently in Nyae Nyae .

In 1959, Tsumkwe was established as an administrative centre by the South West African administration for the Nyae Nyae area, with the aim of it becoming a location for the permanent settlement of the Ju/’hoansi. The promise of employment, food and medical care was made in order to encourage the Ju/’hoansi to leave their land and move to Tsumkwe. Over the first few years following its establishment, approximately 700 Ju/’hoansi moved into Tsumkwe – apparently far more than had been anticipated. This gave rise to probably one of the darkest chapters in the history of the Ju/’hoansi (1973 – 1984). Overcrowding, the lack of employment and access to veld foods, and readily available alcohol in Tsumkwe quickly gave rise to many social, economic and health problems. It is no surprise, therefore, that Tsumkwe came to be known by the Ju/’hoansi as the “place of death”.

The fencing of the Namibia – Botswana border in 1965 effectively divided the Ju/’hoansi down the middle. Further to this, following the 1964 Odendaal Plan, Bushmanland was established as a homeland in 1969. The Ju/’hoansi territory had formerly extended into what is today known as the Khaudum National Park in the north, and what was then known as Hereroland in the south; they were now restricted to less than 10% of this territory, and had lost access to many of their traditional water and food sources.

Many of the decisions taken by the Ju/’hoansi were traditionally inextricably linked to land, the resources found on the land, and finding equitable, mutually acceptable ways of ordering access to these resources. In addition, the Ju/’hoansi also had well defined family links to these resource areas, which they called n!oresi. These n!oresi were “managed” by a n!ore kxao, which translates as n!ore owner or steward. Such ownership or right could not be sold or given away, and was passed on through the family by the parents.

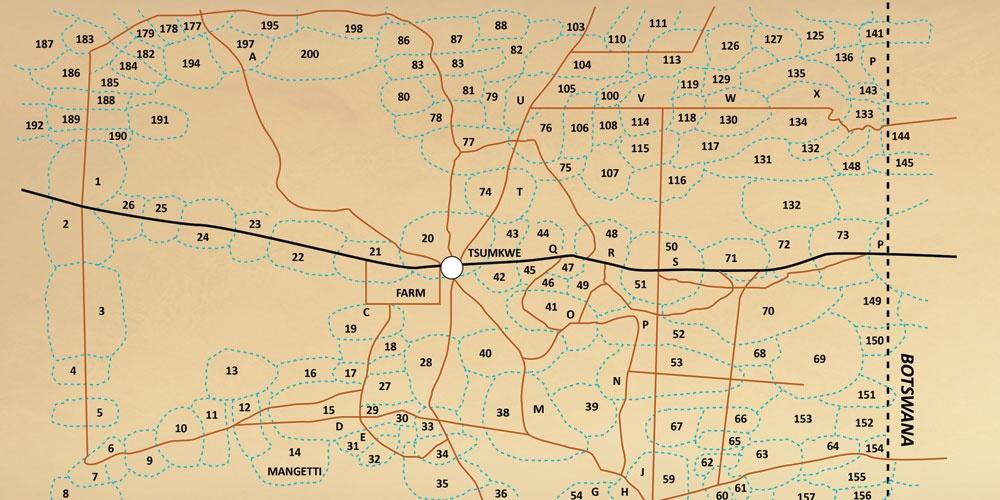

Despite the formation of Bushmanland and other policy decisions that threatened their access to land, the Ju/’hoansi have managed to maintain many of their ancestral n!oresi until today. It is thought that up 300 n!oresi are known to the Ju/hoansi, but only about 200 were mapped in the early 1990s.

N!oresi of the Ju/'hoan San

In 1986, five years after the establishment of the JBDF, the Ju/wa Farmers Union (JFU), a community-based organisation, was established with assistance from the JBDF. This was a defining moment in the history of the Ju/’hoansi, as it brought about a significant shift in the manner in which decisions would henceforth be made. Prior to the formation of the JFU, most decisions were consensus- and principally village-based, and largely focussed on day-to-day issues. The formation of the first community-based representative body, though something quite unknown in their history and culture, was necessary in an ever-changing world, as it now provided the Ju/’hoansi with a collective voice.

In 1988 the JFU reconstituted itself as the Nyae Nyae Farmers’ Cooperative (NNFC). This change was necessary, as it reflected the realities of the time, and responded to the prospect of Namibia’s imminent independence. Then, in 1998 the Nyae Nyae Conservancy was gazetted as the first communal conservancy in Namibia, and the NNFC became known as the Nyae Nyae Conservancy (NNC). A conservancy is a common property resource management institution established by local communities under national legislation for the management, utilisation and the right to benefit from wildlife and tourism. In 2013, NNC was registered as a Community Forest, becoming the Nyae Nyae Conservancy and Community Forest (NNCCF).

Map N#a Jaqna and Nyae Nyae Conservancies

1.3. Who are the San in Namibia

Who are the ‘San’ or ‘Bushmen’? ‘San’ is an all-embracing name given to people from former hunter-gatherer societies, even though they come from different ethnic groups with distinct languages and dialects, some of which cannot be understood by others. It is very difficult to specify exactly which groups of people can be identified as San, as the term ‘San’, like ‘Bushmen’, is one that they did not coin themselves, and they also do not necessarily share any common identity.

In southern Africa, it has been estimated that there are approximately 100 000 San people living in six countries, namely Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa. However, the actual number of San depends to a large extent on the definition of ‘San’, and the racial and ethnic categories established during the apartheid era. Various reports, papers and publications give widely differing estimates of the total number of San.

In Namibia, the San population has been estimated to number between 32 000 and 38 000, comprised of six groups (although some sources refer to ten groups), each with its own language, customs and history. Collectively, they constitute about two per cent of the overall population of Namibia. During the colonial era in Namibia, the former South African administration forcibly evicted most of the San population from land they had occupied for millennia. It has been estimated that 80% of the San have been dispossessed of their ancestral land. Because of this displacement and a long history of marginalisation, the San groups are considered to be amongst the most vulnerable in Namibia. Most San today have little access to employment or reliable sources of income; up to 68% of Namibians speaking one of the Khoisan languages (the majority of whom are San) are considered to be living in poverty. For the San, the prevailing conditions of landlessness, in tandem with a lack of education, renders them more dependent and economically vulnerable than any other group in the country.

2. Development focus areas

This section deals with key focal development initiatives that are considered to have had the most profound long-term impact on the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae. The focus falls on changes in approach and other relevant factors in order to illustrate their impact over time. It is easier to assess the impact of initiatives with the advantage of hindsight than it is to anticipate such impact during planning and implementation; in so doing, the intention is not to criticise or belittle any previous activities that may not have succeeded: they were necessary steps in a process, and without them, subsequent achievements would not have been possible.

2.1. Water

It is something of a cliché to note that “water is life”. For the Ju/’hoansi, however, this could not be truer. In the past, when their territory was vaster by far than it is today, their movements and activities were determined largely by the availability of resources, and primarily by water. The provision of water at each inhabited n!ore has been a priority for the NNDFN.

2.1.1. Provision of water

In the late 1970s and early 80s, the Ju/’hoansi had lost the greater part of their land which was essential to their way of life. This was exacerbated by the atrocious living conditions and associated problems in Tsumkwe, as well as many unkept promises, and it came as no surprise that many of the Ju/’hoansi were more than eager to challenge this state of affairs and return to their land. At the time, many Ju/hoansi elders noted that if they did not move back onto their land and occupy their traditional n!oresi, their remaining land would be lost forever.

One problem amongst many that the Ju/’hoansi faced when in the late 1970s to early 1980s they wanted to move out of Tsumkwe, often referred to as the “place of death”, to their n!oresi, was having access to a secure source of water. Now that their territory had been drastically reduced in size, they were no longer able to move to where water could be found.

In 1984, a small victory was won for the Ju/’hoansi when a hand pump was installed at a borehole drilled by the administration at the village of //Auru. They made known their intention to settle on their traditional n!ore, and not to leave. They insisted that the water and pump belonged to them, and eventually they were allowed to settle in //Auru. This small victory motivated the Ju/’hoansi even further, and the move back to the land started to gain momentum. Between 1984 and early 1992 almost 30 n!oresi became permanently occupied thanks to the provision of boreholes and pumps to extract the water by the NNDFN.

The NNDFN is very important; boreholes are also important because in the past the government and nature conservation almost took our land away from us, they drilled boreholes for wild animals but the NNDFN helped and we said no, the land belongs to the Ju/’hoansi and they should drill boreholes for people.The NNDFN is very important; boreholes are also important because in the past the government and nature conservation almost took our land away from us, they drilled boreholes for wild animals but the NNDFN helped and we said no, the land belongs to the Ju/’hoansi and they should drill boreholes for people.

Chief Tsamkxao ≠Oma

Although there are doubtless many other impacts related to the provision of water, the most important was that the Ju/’hoansi could now permanently settle on their traditional n!oresi. This meant that the land was occupied and being utilised, and must therefore be considered a highly significant step in their endeavour to secure rights to their land.

Boreholes were initially only provided with rudimentary protection against elephants, and they were no match against the strength and desire for water of these animals. This resulted in considerable damage to these water points and infrastructure, which often meant that the lives of village inhabitants were seriously disrupted, as they could be without water for extended periods.

Although the provision of even basic water supply is important in itself, the amount of water that can be extracted is also important, as village inhabitants need greater volumes if they are to keep livestock and maintain their vegetable gardens. During the early years of the movement back to the land, boreholes were mostly equipped with hand pumps. These were reliable, but not efficient enough to sustain successful vegetable gardens or provide water for livestock.

If you don’t have water to live then you are not a person.

Daqm Boo

Boreholes help us to control our land. We used to move around to find water, but now we can stay at our n!oresi and secure our land

G/aq’o ≠Oma

2.1.2. Vegetable gardens

The establishment of dryland crop fields and vegetable gardens has long been a priority for support from the NNDFN, but for a variety of reasons, these initiatives have historically met with limited success.

Both were seen as essential for food security if the Ju/’hoansi were to sustain themselves and remain permanently settled at the villages. With only a few exceptions, early attempts at establishing vegetable gardens never took root. Several critical factors can be identified as having contributed to this failure.

Water supply was often interrupted when elephant damaged the water infrastructure. Early attempts to deter elephants with railway sleepers and ditches failed. Plants subsequently withered and died, leading to despondency amongst inhabitants.

- Few villages had appropriate water storage facilities, so gardens failed when there was not sufficient water.

- Vegetable gardens were established on a communal basis. This diluted the sense of ownership, and thus diminished responsibility and accountability.

- Most Ju/’hoansi had no prior experience of agricultural activities.

Today, however, there is a renewed drive towards the establishment of vegetable gardens in many of the villages in Nyae Nyae. A number of critical factors can now be identified as having contributed to this.

- During the early 2000s, the NNDFN re-embarked on a massive undertaking to ensure that village water sources were adequately protected against potential elephant damage with the construction of large rock walls around water infrastructure. There are now 36 villages that have water sources that are both reliable and fully protected.

- In all of these villages, water extraction methods are now suited to the different borehole conditions, and most have solar-powered submersible pumps.

- In the last 7 years all villages have been provided with suitable water storage facilities located within the elephant protection area.

- Support for the establishment of gardens is now given to individuals and households in selected villages to those that show interest, rather than to everyone in all villages. This has empowered those who actually want to establish gardens, enabling them to directly reap the benefits from the gardens once they are producing

- Careful consideration has also been given to the selection of appropriate plant varieties for the vegetable gardens. They must not only be adapted to local conditions, but must also be culturally acceptable to the Ju/’hoansi, and make the greatest impact on nutrition. Sweet potatoes, melons and gourds, for example, have ticked all the boxes, and proven to be extremely popular.

- The provision of information and training has contributed greatly to the shift in attitudes towards agricultural activities by the Ju/’hoansi resulting in more uptake and sustainability. Initial training is followed up with visits to successful villages and sustained support, often by local San ‘Champions’, who can help deal with ongoing issues as well as initiate different planting seasons.The provision of information and training has contributed greatly to the shift in attitudes towards agricultural activities by the Ju/’hoansi resulting in more uptake and sustainability. Initial training is followed up with visits to successful villages and sustained support, often by local San ‘Champions’, who can help deal with ongoing issues as well as initiate different planting seasons.

- Promoting permaculture including the use of cattle manure and composting as a means of making gardens more productive. Crop rotation, co-planting to deter pests and trees for shade, ground cover and fruit to provide additional nutrients.

Today, excess production, for example of sweet potatoes, is being sold by farmers to generate much-needed cash income. This would not have been the case some years ago.

Improving our livelihoods, clean water and food security are priorities for the future. We need training and projects so that people can realise that they can improve their lives.

Xoa//’an /Ai!ae (NNCCF Chair)

The NNDFN’s experience and recent successes with vegetable gardens demonstrate how minor shifts in approach can lead to greater engagement in initiatives. Because of the provision of a reliable source of water and a shift in approach, some vegetable gardens are now starting to thrive and make a difference to nutrition. The villagers are directly benefiting from the fruits of their own labour, and the importance of the positive reinforcement that this provides should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, previous less successful attempts at establishing vegetable gardens, for example, should not be seen as a waste of time or as failures, as they provided the foundation and impetus for subsequent successful adoption.

2.1.3 Livestock

Similar to vegetable gardens, NNDFN support for livestock initiatives has long been a goal, as witnessed by the establishment of the Cattle Fund, in order to provide support for basic economic elements to enable the Ju/’hoansi to subsist at a village level.

Since the formation of the Cattle Fund, the Ju/’hoansi have acquired livestock, mainly cattle, provided by various support organisations, but primarily through the efforts of the NNDFN. However, attempts to stimulate sound livestock management practices were met with varying levels of success. In some early cases, livestock were slaughtered in times of hardship, while many were killed by predators, mostly lions; the lack of water also resulted in mortalities. Again, animal husbandry was considered to be a new concept for the Ju/’hoansi, and proper livestock management was consequently not something that came naturally. Nevertheless, some Ju/’hoansi did manage to build up small herds.

Current livestock support provided by the NNDFN is based on holistic rangeland management principles. This programme was initiated in response to community requests for cattle, and was piloted in four villages that already had cattle, and were thus predisposed to embrace better livestock management practices. The overall purpose of the programme is to improve livestock health, fertility and survival as well as preventing overgrazing. A key activity has been the introduction of planned grazing and herding, which has resulted in reduced calf mortalities, reduced deaths from predators and poisonous plants and improved overall livestock health brought about by ensuring that sufficient water is available and that animals are grazing in areas where the grass is the most nutritious, then allowing enough time for grass to recover before returning. An indirect positive result has been that milk production has also increased, making more available for human consumption. There are now 12 villages practising planned grazing and herding on a sustained basis.

So what factors have been responsible for bringing about positive change?

- In the early stages of the current programme, support was provided only to individuals or household farmers who were already engaged in livestock farming, and who therefore had a vested interest in the programme succeeding. Significant consultation, materials and advisory support were provided to these villages for several years in order for the benefits to be apparent and sufficient to motivate a sustained effort from the farmers and their herders.

- To maintain herder engagement, those herders showing long-term dedication to the process were provided with a cow in order for them to start their own herd and motivate continued interest in herding.

- To improve the genetics of herds, as inbreeding was felt to be leading to blind, weak calves being born, twelve new bulls were introduced over five years and are rotated every two years as necessary. Those receiving bulls have agreed to provide a young male offspring to improve the genetic mix in other villages. Four villages have so far provided a young male to other villages to sustain genetic diversity.

- The water supply for livestock has been improved. Water points have been adequately protected against elephants and storage tanks have been installed, ensuring reliable water availability as never before.

The current approach to livestock management is being undertaken in conjunction with other activities, and in particular with those related to the establishment of vegetable gardens, where the Ju/’hoansi are encouraged to use cattle manure. - The support being provided has been expanded to four villages that did not previously have cattle, thereby establishing new herds. These villages were assessed for their suitability and commitment and then a herder was selected to herd the ‘new herd’ with one of the existing successful villages in order to gain skills and experience for six to nine months, before the herd is returned to its “home” village.

- The provision of support is still directed to where it is most likely to succeed, and support has been withdrawn from two villages where commitment was lacking and resources wasted.

The Ju/’hoansi have always emphasised the importance of maintaining “the health of the land”. Many early opponents to providing the Ju/’hoansi with cattle were concerned that the livestock would degrade the land, but this has not happened. Herds have been relatively small and widely dispersed, but more importantly, the Ju/’hoansi have been proactive in establishing guidelines to promote conservation and sustainable development, and prevent over-exploitation.

Boreholes help to protect the land by living on the land, water allows us to do other things and makes life easier, now we don’t have to go and look for water, now the only struggle is to find enough food.

Daqm Boo

2.2. Land

The area of what is today known as Nyae Nyae is about a tenth of the area which the Ju/’hoansi formerly occupied, as recently as the 1950s. This was largely as a result of the creation of the Bushmanland homeland in 1969, because of the fencing of the border between Namibia and Botswana. The relationship between the Ju/’hoansi and land has always been, and continues to be characterised by respect. The knowledge that the resources the land provided were responsible for sustaining their lives resulted in the realisation that the land was something that needed to be taken care of.

The provision of water was instrumental in enabling the Ju/’hoansi to move back to their land and inhabit their traditional n!oresi. Although this did not in itself guarantee them any substantive rights over their land, it did, however, provide a very important platform. The land situation for the Ju/’hoansi today, although much improved, as discussed below, is still not assured, and is constantly being eroded at many levels.

The NNDFN has since its formation always seen unfettered access to the land the Ju/’hoansi have inhabited for millennia as a critical foundation for them to be able to assert their right to self-determination. The NNDFN has been closely involved in advancing Ju/’hoansi land rights. While other factors have also played a role, three main events can be identified as having contributed to this process.

2.2.1 Land reform and the land question conference

The first was the Land Reform and the Land Question Conference that was held in Windhoek in June-July 1991, shortly after Namibia had gained independence in 1990. The NNDFN and the NNFC supported the Ju/’hoansi ensuring their vocal participation in and representation at the conference. Through well prepared and balanced presentations, the NNFC contributed to getting communal forms of land tenure accepted as a basis for moving the land question forward in Namibia. In addition, the conference resolutions also recognised by unanimous decision that “San” land rights should be afforded special protection.

Unfortunately, many of the gains made at this conference were short-lived, as despite follow-up conferences and meetings, there was a failure to formalise the outcomes. Sadly, the land question still remains unanswered, not only for the Ju/’hoansi, but also for many others living in Namibia.

2.2.2 The Nyae Nyae Conservancy

The second opportunity for support action was provided by a shift in approach towards conservation in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a result of the adoption of the policy of Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism as a tool to promote conservation, while enabling inhabitants of a particular area to also benefit from its resources, notably wildlife.

Given the failure of the Namibian Land Reform Conference to bring about meaningful changes, the NNDFN and the NNFC took a strategic decision to assess the viability of establishing Nyae Nyae as a conservancy. This decision was prompted by the inaction of the government regarding the land question, and explicit statements by external groups of people indicating their desire to settle with their livestock in the Nyae Nyae area, both of which constituted ongoing threats to Nyae Nyae and the livelihoods of the Ju/’hoansi.

The Nature Conservation (Amendment) Act No 5 of 1996 was then promulgated allowing for communal conservancies to be established. As a result, following a long process of consultation and planning, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy was formally gazetted in June 1998. The formation of the NNC provides the Ju/’hoansi with management and utilisation rights over wildlife- and tourism-related activities from which they can benefit. An important aspect of the formation of the conservancy was the required inclusion of a management plan and a zonation map specifying land uses in particular areas of Nyae Nyae. Although not providing absolute guarantees, these do provide a measure of control over what happens in the Nyae Nyae area.

As is so often the case, hindsight invited conflicting views on what could have and should have been done. There were numerous debates and disagreements about the NNDFN having promoted CBNRM in Nyae Nyae, supposedly at the expense of livestock and small-scale farming, some of which are described in the film “A Kalahari Family”. It is doubtful, however, that livestock and crop production alone would have secured as much control over their land as the conservancy has done, or indeed that those efforts would have succeeded given the lack of secure water and storage in villages at that time. It is also doubtful whether livestock and crop production would have been able to generate the income the conservancy manages to earn from wildlife- and tourism-related activities today. The NNC is one of the few self-funding conservancies in Namibia today, and is one of the largest employers of the Ju/’hoansi in Nyae Nyae. The NNC structure required support at that time in order to be established and now the community are benefiting from a more diverse range of income and livelihood sources as both wildlife activities and livestock/agricultural activities exist side by side.

The conservancy must continue to live, we have not fenced off places and wildlife can move freely, we need to increase wildlife. If the conservancy fails there will be no more wildlife, no tourists, no income, and many things we have built up will collapseThe conservancy must continue to live, we have not fenced off places and wildlife can move freely, we need to increase wildlife. If the conservancy fails there will be no more wildlife, no tourists, no income, and many things we have built up will collapse

Chief Tsamkxao ≠Oma

2.2.3 Community forest

The third area of support was provided by the opportunity created by the promulgation of the Forest Act, No. 12 of 2001, revised in 2005. This legislation allowed for the establishment of community forests, much like conservancies.

A community forest is an area in the communal lands of Namibia for which local communities have obtained the rights to manage forests, woodlands and natural vegetation. The community forest management is guided by the principles of sustainable management by local communities in order to protect forest and tree resources and improve livelihoods. While the focus is on managing wood and non-timber resources, the intention is to also to complement the management of game resources in communal conservancies with the management of natural vegetation and habitats, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive natural resources management strategy.

Community forests provide a mechanism through which communities can utilise, benefit from, and protect forest resources, grazing being one such resource. The NNDFN considered the community forest legislation to be important as a means of securing further rights for the Ju/’hoansi to their land, as it provided a basis for regulating the threat posed by pastoralists from outside Nyae Nyae. The NNDFN provided technical support to the NNC in the planning and consultation phase of establishing Nyae Nyae as a community forest. In March 2013, the Nyae Nyae area was gazetted as the Nyae Nyae Community Forest (NNCF). The boundaries of the NNCF exactly followed those of the NNC, and the constitution was designed to allow for the same management structures to continue to exist, and to manage both wildlife and forest resources.

2.2.4 Recognition of the traditional authority

A final important issue related to the land question in which the NNDFN played a role was the official recognition of the Ju/’hoansi Traditional Authority in 1998 under the Traditional Authorities Act of 1995. Having in the past had no such institution or leader, the Ju/’hoansi, together with the NNDFN, set about wide consultations within the community.

This led to the democratic election of Tsamkxao ≠Oma, or Chief Bobo as he is more affectionately known, as the first Chief of the Ju/’hoansi. He was the son of ≠Oma Tsamkxao, an inspirational person who had been at the forefront of the campaign of the Ju/’hoansi to return to the land in the early 1980s. Chief Bobo had also been elected in 1986 as the first chairperson of the Ju/wa Farmers Union, and subsequently of the NNFC, in which position he remained until 1991, when a new chairperson was elected. He nevertheless continued to play an important role in the NNFC as president until he was elected as Chief.

At first, none of the San communities who had applied for official recognition were approved by the government. A formal complaint was lodged, and following reconsideration, two San communities, the Ju/hoansi in Tsumkwe East District, and the !Kung and Khwe in Tsumkwe West District, were officially recognised by the government at that time. This recognition was based almost entirely on the fact that these communities retained a portion of the land base which they had traditionally inhabited.

The recognition was important for three reasons: firstly, it recognised that the Ju/’hoansi did in fact have traditional land; and secondly, through the powers vested in the Traditional Authority, it afforded the Ju/’hoansi greater control over what they could do in the area they inhabited.

In addition the Ju/’hoansi through the Traditional Authority are represented on the Otjozondjupa Communal Land Board. The Communal Land Reform Act (Section 31(4)) prohibits this body from granting leaseholds which would defeat the purpose of the Game Management and Wildlife Utilisation Plan of the NNCCF.

2.2.5 The sustainable use of land and resources

The Ju/’hoansi face a complicated challenge with respect to asserting their rights over the land in what is today known as Nyae Nyae. In spite of their traditional and cultural heritage and the rights accorded them under conservancy and community forest legislation, there is a misconception that areas of Nyae Nyae are underutilised because it has not been over-grazed and that others should have access to the land.

The Ju/’hoansi face a complicated challenge with respect to asserting their rights over the land in what is today known as Nyae Nyae. In spite of their traditional and cultural heritage and the rights accorded them under conservancy and community forest legislation, there is a misconception that areas of Nyae Nyae are underutilised because it has not been over-grazed and that others should have access to the land.

The assertion that open or empty land is not being utilised by the Ju/’hoansi is wrong. The n!ore system of land allocation used by the Ju/’hoansi for millennia provides access to land for hunting, the collection of “veld food”, and more recently, livestock production. The intimate relationship that exists between the Ju/’hoansi and their environment is inextricably linked to the n!ore system. It is in no way a paternalistic or romanticised notion that their knowledge of the Nyae Nyae environment and its sustainable utilisation is second to none in both its breadth and its intricacy. This can be witnessed in their in-depth knowledge of plants and their uses, which range from food, medicine, poisons and hunting equipment, to construction materials, tools, cosmetics, items used in cultural rituals, musical instruments, and more.

The Ju/’hoansi have adopted an integrated approach to the utilisation of their land which is reflected in the core objectives of their conservancy and community forest. This approach enables them to benefit from wildlife and related activities, from livestock and other natural resources. The underlying principle is as far as possible only to undertake activities that have minimal environmental impact.

“I don’t have a car, money or anything – I depend on the area (Nyae Nyae) for wild game, veld food, and therefore we must handle this land with care. The land is the source of life, it allows us to live. In the past, people did not finish the resources, so we still have those resources today. ”

Daqm Boo

This approach adopted by the Ju/’hoansi is an excellent example of resource management being the responsibility of those living with and utilising the resources. The underlying rationale is that the management of natural resources is best left in the hands of those who have a direct interest in the sustainability of the resources upon which they depend, and that this entails giving the resources a focused value.

The sustainable harvesting and sale of devil’s claw by members of the NNCCF is a good example of a resource having been given a monetary value. The income from this activity makes a significant contribution to improving the livelihoods of the Ju/’hoansi involved.

Devil’s claw grows mainly in the deep Kalahari sands that extend through the Nyae Naye area. Many indigenous peoples of southern Africa, in particular San groups like the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae, have for centuries made use of devil’s claw tubers for medicinal purposes. Ethno-medicinal uses have been recorded mostly for digestive disorders, fever, sores, ulcers and boils, and as an analgesic drug. It is only in the last 50 years, however, that the medicinal value of devil’s claw for the treatment of rheumatism, arthritis and other similar ailments has been recognised by Western medicine. The devil’s claw plant has a main taproot off which secondary storage tubers extend, and it is these tubers that contain the highest concentrations of the active ingredients, which are used for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties.

The basis for the harvesting and sale of devil’s claw from Nyae Nyae is provided by the activation and organisation of groups of village- or n!ore-based registered harvesters. Harvesters engage in an exchange of knowledge on sustainable resource use, and voluntarily adopt sustainable resource management practices which they have helped to formulate. Monitoring of the harvesting and processing helps them to ensure compliance with sustainable harvesting techniques and the maintenance of quality standards. The devil’s claw from Nyae Nyae is also certified organic, which guarantees that certain standards have been met, allowing for higher prices to be paid directly to harvesters.

The approach in Nyae Nyae includes the following key features:

- Training and registration of harvesters who apply for a group permit

- A management system for quality control and record keeping that guarantees product traceability

- Sustainable harvesting methods, compliance which is ensured through harvest monitoring and post-harvest impact assessments

- A contract with a reliable Namibian exporter, which secures a market and access to market information

- Premium prices paid directly to harvesters

A critical element of the Ju/’hoansi’s devil’s claw trade is that the harvesters are paid directly by the buyer, receiving over 80% of the total sales value. In 2015 and 2016 up to three hundred harvesters have earned close to 1 million Namibia dollars. In an area which is almost devoid of employment prospects, this income is an important source of much-needed supplementary cash.

As with the use of other resources in Nyae Nyae, sustainability is vital, and the Ju/’hoansi harvesters recognise its importance for enabling them to continue to benefit from the harvesting and sale of devil’s claw in the future. Ensuring the health and survival of the devil’s claw’s resource at a higher level requires the maintenance of the balance of the entire ecosystem of these supposedly underutilised, “empty” areas.

The harvesting of and trade in devil’s claw offers one of very few opportunities for the Ju/’hoansi to generate much-needed cash income; these benefits are available only for a limited season, and are dependent on environmental conditions. If there is to be any substantial improvement in the livelihoods of the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae, the creation of other income-generating opportunities to supplement the benefits obtained from devil’s claw must enjoy urgent and ongoing attention.

Thus, perceptions that the Nyae Nyae area is underutilised are dangerously misplaced. The area is differently used to other communal areas in Namibia with the San taking responsibility for sustainable use of available resources. Most other communal areas in Namibia have been over-grazed and de-forested due to a lack of understanding of the environment and/or competitive unsustainable use of resources amongst communities.

We need to protect the land against illegal settlers and grazers, and the unsustainable harvesting of devil’s claw to move forwardWe need to protect the land against illegal settlers and grazers, and the unsustainable harvesting of devil’s claw to move forward

Chief Tsamkxao ≠Oma

2.3 A voice

“In Namibia, we all have our rights, before the NNDFN we did not talk about things or make plans, but then the NNDFN helped to bring people together to talk about the future … it helped us to find a voice.”

/’Angn!ao /’Un (known as Kiewiet, the first NNC Chairperson)

The NNDFN has played an important role in advancing the interests of the Ju/’hoansi by supporting their struggle to move back to the land, acquire reliable water sources and secure important, albeit limited, rights over their land and resources. A less obvious, though equally valuable contribution, however, has been that it has promoted the voice of the Ju/’hoansi. NNDFN has also served as a catalyst for the Ju/’hoansi to find their own voice through what is today known as the Nyae Nyae Conservancy and Community Forest. A key objective of NNDFN has always been empowering the Ju/’hoansi to help and represent themselves.

In the late 1970s, many Ju/’hoansi living in Tsumkwe openly stated that they wanted to return to their traditional n!oresi. However, the resources needed to do this – and more importantly, the means to remain on the land – were altogether lacking. In responding to this need, the Cattle Fund was established in 1981, soon thereafter becoming the Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation. Its purpose was to assist those Ju/’hoansi who wanted to move back to their land by providing them with livestock, tools and seeds, with the aim of creating a means by which the Ju/’hoansi could sustain themselves in their n!oresi. These organisations were the first representative bodies of this community, which was a new concept in the Ju/’hoansi culture and provided a collective voice for the community.

NNDFN support to the Ju/’hoansi in the 1980s thus focussed on assisting them to move back to their n!oresi, providing them with livestock, tools and seeds, and drilling boreholes and installing the necessary equipment such as windmills, hand pumps and water tanks that would ensure reliable access to water. This required their voice to be heard in various forums and often NNDFN became the voice or significantly coached representatives from the community in being vocal about what the community wanted, thus enabling the necessary funding and support to be secured.

The 1990s saw substantial growth in the support provided to the people of Nyae Nyae. The establishment of the Baraka Training Centre in 1991 improved the delivery of training and development support. The number of NNDFN staff increased considerably, as did the number of support programmes, and a larger, multi-faceted Integrated Rural Development Programme was initiated. Support under this programme targeted primary healthcare, income generation, village schools, village gardens, livestock, the ongoing provision of water, mechanisms for securing land in independentNamibia as well as a leadership programme to try and build the capacity and voice of the community’s representatives.Namibia as well as a leadership programme to try and build the capacity and voice of the community’s representatives.

At the same time the principles and practices of what is today known as CBNRM were gaining acceptance as a means of providing both development opportunities for rural communities, and mechanisms for safeguarding natural resources. The underlying assumption of CBNRM is that if people can benefit from wildlife and plant resources in the areas where they live, they will be more inclined to protect them. After independence, Namibia also adopted the CBNRM approach, and legislation was enacted to make provision for the establishment of communal conservancies, much the same as was already the case on the private commercial farms in Namibia. The NNDFN also adopted this approach in Nyae Nyae as one means of securing additional rights for the Ju/’hoansi. While various other projects continued to be implemented, consultations and planning began in earnest with a view to the establishment of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy (NNC) . With the formation of the NNC in 1998, the first such communal conservancy to be registered in Namibia, much of the development focus of the NNDFN now centred on issues related to wildlife and tourism, and the associated benefits that they could deliver. The Chairperson and Manager of the conservancy also became key voices for the community.

Since then, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, and since 2013, the Community Forest has become increasingly self-sustaining and financially independent, to the point of being one of the few conservancies in Namibia that is able to annually generate sufficient income to fund its own activities.

This has strengthened the position of the community and their ability to be heard. NNDFN supports the NNCCF in making its own decisions and to learn from making those decisions. Although the NNDFN still provides some advice and support to the conservancy in the form of financial administration, planning and mentoring, the NNDFN has been able to step back and let the conservancy run its own affairs.This has freed up the NNDFN to concentrate on providing more targeted village-based individual and household livelihood support. The approach is now to endeavour to reduce the dependency created by formerly attempting to provide equal support for all. A shift from wholesale, en masse project support to a more individual- or household-based support is now being pursued. The rationale behind this is that support that is provided to those that have the capacity and motivation to undertake certain activities is more likely to be sustainable in the long term. This is ultimately more empowering as more individual and household responsibility and accountability are fostered, they will be more likely independently adopted by others.

In the last few years, NNDFN has engaged help in liaising with the media in order to raise the profile of some of the issues, particularly illegal land and resource use, which the government and its authorities are failing to address. This has proven to be more effective in motivating a response from relevant ministries than attempting to liaise with them via letters or their offices. In addition, a concerted effort has been made to put positive stories of the San in the press covering their achievements and areas where they are helping themselves in order to start improving perceptions of the San.

2.3.1 Other voices - The Legal Assistance Centre

The NNDFN has not been the only voice for the Ju/’hoansi. There have been many others who have made important contributions at many levels and in different ways towards ensuring that the voice of the Ju/’hoansi is heard.

Against the background of the extent of the marginalisation that the Ju/’hoansi have faced and continue to face, legal representation is a particularly important aspect of the support provided. One organisation that has contributed significantly in this regard is the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC). Founded in 1988, the LAC’s main objective is to protect the human rights of all Namibians by making the law accessible to all, and especially to those whose access is the most tenuous.

Communal conservancies were established in 1996 through an Act of Parliament; however, members of such conservancies typically had little if any access to legal representation. As a result, the LAC initiated the Conservancy Support Programme to provide training to conservancies, conservancy support organisations, local authorities and other stakeholders, and to give legal advice and advocacy on conservancy issues. The LAC thus provides much-needed legal advice to conservancies and community forests, at no cost.

The NNDFN has also managed to independently raise funding which enables it to retain the consultancy services of the LAC. The LAC has been instrumental in facilitating the development and review of conservancy and community forest constitutions and related legal documents. In Nyae Nyae, together with the NNDFN, the LAC has been proactive in ensuring that the Ju/’hoansi and the NNCCF have legal representation concerning illegal land occupation and grazing of livestock by non-members of the NNCCF. Illegal grazing is a serious matter in Nyae Nyae, as it erodes the foundation of natural resources management to which the Ju/’hoansi have committed themselves, and runs counter to the sustainable utilisation of the resources found in the area.

Without the NNDFN we would still be controlled by the government, but now we control ourselves.Without the NNDFN we would still be controlled by the government, but now we control ourselves.

/’Angn!ao /’Un (known as Kiewiet, the first NNC Chairperson)

3. Reflections & challenges

3.1 Reflections

This section does not attempt to cover all of the lessons and reflections that have emerged from the 36 years of NNDFN engagement with the Ju/’hoansi in Nyae Nyae. Rather, it is a selection of more recent lessons that are relevant to current circumstances, and which can assist with implementation.

Development cannot be measured in project cycles. An important lesson that emerges from this publication is that the consistency of ongoing support provided by the NNDFN over the last 36 years is more significant than the outcomes of individual programmes. Change does not happen overnight and the consistency of support has been key to many of the achievements of the NNDFN and the Ju/’hoansi. Desired outcomes are sometimes only realised long after the initial interventions and are important in that they provided a foundation on which to build in the future.

Development cannot be measured in project cycles. An important lesson that emerges from this publication is that the consistency of ongoing support provided by the NNDFN over the last 36 years is more significant than the outcomes of individual programmes. Change does not happen overnight and the consistency of support has been key to many of the achievements of the NNDFN and the Ju/’hoansi. Desired outcomes are sometimes only realised long after the initial interventions and are important in that they provided a foundation on which to build in the future.

An important aspect connected to the consistency of support provided is that viewpoints and agendas change over time. These changes are important as they bring about shifts in outlook towards project implementation and the uptake of certain activities. It is essential that appropriate infrastructure and facilities are available to take advantage of these changes. A good example of this is the changes that have taken place with regards to the approach to livestock management. When the NNDFN first started with livestock provision in the 1980s, animal husbandry was considered to be a new concept for the Ju/’hoansi. This has changed, however, and the Ju/’hoansi are now embracing the concept of village-based combined herding of cattle and are realising the associated benefits for herd health and the environment.

The timing of the implementation of different projects is crucial. This is something that is often outside of one’s own control. There are multifaceted, broader issues at play that can have a considerable influence over the outcome of any individual project within the overall support programme. A project implemented at one time may yield a different outcome to the same project implemented at a different time. A thorough consultation process is therefore essential, and if possible, pilot projects should precede full-scale project implementation, as they can play an important role in guiding such implementation and ensuring the success of the project.

The training and experience from all the projects has helped to change attitudes. Change is slow, after some time you realise that you should have done something at that time.

≠Oma Tsamkxao

While there are many factors that influence uptake, the recent resurgence in the establishment of vegetable gardens and developing a more permaculture based approach clearly illustrates the importance of project timing. Previous initiatives had largely failed because adequate water storage facilities, which are essential for vegetable gardens, had been lacking.

Take a flexible approach. There is a need to remain flexible and learn from the implementation of different projects, and have the courage to adapt one’s approach and to focus on a few essential areas for a sustained period. It is also not necessary to ‘put all your eggs in one basket’, as previous debates about wildlife versus livestock failed to see the greater benefit of having both.

Some projects do not always lend themselves to wide-spread roll-out. The mode of implementation of support programmes sometimes needs to be adjusted in response to altered circumstances or between different locations. The focus of some NNDFN projects has shifted over time from community-wide support towards support that is more targeted at individuals and households and those showing commitment, resulting in a clear improvement in outcomes. The shift in approach from a communal focus to an individual and household focus with respect to vegetable gardens and livestock is a good example of this phenomenon. NNDFN has also moved away from defining a standard working relationship with all project sites, rather allowing the varying nature of different locations and people define what works best for them.

There is a fine line between enabling responsibility and usurping responsibility. NNDFN actively strives to ensure that the support that it provides is focussed on allowing the Ju/’hoansi to make their own decisions and lead processes themselves. For example, in providing organisational management support, the NNDFN endeavours to play a mentoring role and provide guidance in terms of compliance with regulations. Beyond legal compliance, It is important to allow communities to decide on their own future, at their own pace and learn for themselves as they go.

Play it straight with donors. When engaging with donors, and indeed all other partners too, it is essential to be open and honest about what one is attempting to undertake, and to set realistic targets. A key to the success of the NNDFN in securing long-term funding is that it has been responsive to trends in donor policies, funding opportunities, and economic realities, without compromising the integrity of its overall aims and objectives. The NNDFN has built itself around the principles of accountability, responsibility, transparency and flexibility, and donors recognise and endorse these core values.

“The NNDFN should continue to assist us, helping us with lawyers, projects and training, and find new ways of assisting us such as bringing good investors”

Chief Tsamkxao ≠Oma

3.2 Challenges

“ If you are going to make plans for the future, then it is very important to know where you have come from, so that we don’t lose our culture … Change is slow, one needs to know where you come from to know where to go ”

/’Angn!ao /’Un (known as ‘Kiewiet’ the first NNC Chairperson)

There are a number of important fundamental challenges that the NNDFN and in particular the Ju/’hoansi themselves will need to address if there is to be any long-term progress towards the goal of their not only surviving, but prospering on the land of their ancestors.

Security, especially land tenure, will be required for the Ju/’hoansi to integrate as equal, fully participating partners in the broader Namibian society. Security provides the foundation on which important long-term and far-reaching decisions about their future can be made. The Ju/’hoansi are a community in rapid transition, undergoing radical change in the span of a single generation. How the Ju/’hoansi deal with external and internal community challenges created in part by the rapid transformation process, will profoundly influence their future prospects. The way the community decides to deal with these challenges is directly relevant to the support provided by NNDFN and others.

A current external threat to the Ju/’hoansi’s rights over their land is the problem of livestock owners in Tsumkwe who are illegally grazing their livestock within the boundaries of the conservancy. Threats such as this have in the past been major challenges that had to be faced by the Ju/’hoansi and their support organisations such as the NNDFN, and this is unlikely to change any time soon. Such threats will only serve to escalate the demands placed on the Ju/’hoansi as they strive to assert their rights over their ancestral land. Meaningful development presupposes security; without secure land tenure as a foundation, the content and path of “development” will always be uncertain.

“Today young people find it difficult to leave town (Tsumkwe) – they enjoy it, there is nothing to do in the village for young people.”

Di//xao ≠Oma

Development cannot be understood in isolation, as it is multi-faceted, and involves different development partners whose respective agendas might not always perfectly overlap. Although this is not a new issue, it remains relevant to the situation in Nyae Nyae. Development projects, for example, should complement rather than compete with one another. Parallel developmental initiatives should be encouraged, and coordinated. In this regard, attention will have to be given to obtaining buy-in from other development partners, in particular the government. Creating a shared understanding and vision of what constitutes “development” in the Nyae Nyae area will be crucial in moving forward.

It is important not to assume the responsibility that rightfully resides with the Ju/’hoansi themselves. Organisations such as the NNDFN need to encourage the Ju/’hoansi and their leadership to persist in asserting themselves and voicing their opinions even if they conflict with the views of others. Support for the Ju/’hoansi to strengthen and maintain their leadership must be seen as a priority. This includes, for example, working towards ensuring that the NNCCF’s organisational capacity is sufficient to deal with the numerous issues associated with both day-to-day management and long-term strategic planning. Given that until recently, hierarchical leadership and associated societal nuances were unknown to the Ju/’hoansi, this will remain a challenge for the foreseeable future.

Ensuring water and food security are vital cross-cutting challenges for the Ju/’hoansi. Climate change is also likely to negatively affect the availability of veld food, which still plays a critical role in providing much-needed nutrition. Although much progress has been made with respect to water infrastructure and agriculture, there is still much to be done in order to ensure sustained water and food security for the Ju/’hoansi. Beyond basic water and food security, the challenge is also about identifying other sustainable livelihood opportunities through which the Ju/’hoansi can be further empowered.

Finally, NNDFN must secure funding for the foreseeable future, so that it can continue to support the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae in securing their Water, Land and Voice.

“Providing clean water remains a priority for us (conservancy management) and we need to pay attention to it – it supports life. We need to ensure that our people (the Ju/’hoansi) don’t go hungry and that they remain healthy.”“Providing clean water remains a priority for us (conservancy management) and we need to pay attention to it – it supports life. We need to ensure that our people (the Ju/’hoansi) don’t go hungry and that they remain healthy.”

Gerrie Cwi

References

- Namibia Statistics Agency. 2012. Poverty Dynamics in Namibia: A comparative study using the 1993/94, 2003/04 and the 2009/10 NHIES surveys. Windhoek, Namibia

- Ute Dieckmann. 2011. Update 2011 – Namibia. Yearbook article, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. www.iwgia.org/regions/agrica/namibia/881-update-2011-namibia

- Leffers, Arno, 2003. Gemsbok Bean & Kalahari Truffle, Traditional plant use by the Ju/’hoansi in north-eastern Namibia, Gamsberg Macmillan

- Suzman, James, 2001, An Assessment of The Status of the San in Namibia, report 4 of 5, Legal Assistance Centre

- Biesele, Megan and Robert K. Hitchcock (2011) The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa. Berghahn Books.

- Legal Assistance Centre & Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 2014, Scraping the Pot, San in Namibia two decades after Independence, Ute Dieckmann, Maarit Thiem, Erik Dirkx, Jennifer Hays (Eds)

Suggested further reading

- Hays, Jennifer (2016) Owners of Learning: The Nyae Nyae Village Schools Over Twenty-Five Years. Basel, Switzerland: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

- Hays, Jennifer, Maarit Thiem, and Brian T.B. Jones (2014) Otjozondjupa Region. In “Scraping the Pot”: San in Namibia Two Decades after Independence, Ute Dieckmann, Maarit Thiem, Eric Dirkx and Jennifer Hays, eds. pp. 98-172. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia.

- Hitchcock, Robert K. (2017) Ecotourism, Heritage Tourism and Community-based Development in a Southern African Borderland. In The Ambiguous Art of Ethnoentertainment: Living Museums and Cultural Villages in Namibia, Werner Zips and Manuela Mairitsch-Zips, eds. Wien: Universitat Wien, Vienna, Austria.

- Lee, Richard B. (2016) ‘In the Bush the Food is Free”: The Ju/’hoansi of Tsumkwe in the 21st Century. In 21st Century Hunting and Gathering, Brian F. Codding and Karen L. Kramer, eds. pp. 62-87. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press and Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Marshall, John (2003) A Kalahari Family. (Film) Watertown: Documentary Educational Resources (DER).

- Marshall, John and Claire Ritchie (1984) Where Are the Ju/Wasi of Nyae Nyae? Changes in a Bushman Society: 1958 1981. Communications No. 9, Centre for African Area Studies, University of Cape Town. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Marshall, Lorna (1976) The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Nyae Nyae Conservancy and Community Forest, M’kata Community Forest, and N≠a Jaqna Conservancy (2017) Community-Based Fire Management Training Manual. Windhoek: Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia.

- Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (2015) Dealing with Climate Change in N≠a Jaqna and Nyae Nyae Conservancy and Community Forest. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism and Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN).

- Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (2016) San Community as an integral part of Namibia’s development plans. Windhoek: Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN).

- Suzman, James (2017) Affluence without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen. New York: Bloomsbury USA.

- Thoma, Axel and Janine Piek (1997) Customary Law and Traditional Authority of the San. Centre for Applied Social Sciences Paper. No. 36. Windhoek, Namibia: Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University of Namibia.

- Weinberg, Paul (2017) Traces and Tracks: A Thirty-Year Journey with the San. Auckland, South Africa: Jacana Media.

- Wiessner, Polly (2003) Owners of the Future? Calories, Cash, Casualties, and Self-Sufficiency in the Nyae Nyae Area between 1996 and 2003. Visual Anthropology Review 19(1-2):149-159.

- Wiessner, Polly W. (2014) Embers of Society: Firelight Talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(39):14027-14035.